Hacking into Internet Connected Light Bulbs

The subject of this blog, the LIFX light bulb, bills itself as the light bulb reinvented; a “WiFi enabled multi-color, energy efficient LED light bulb” that can be controlled from a smartphone [1]. We chose to investigate this device due to its use of emerging wireless network protocols, the way it came to market and its appeal to the technophile in all of us.

This blog post was originally published on the Context Information Security blog at https://www.contextis.com/en/blog/hacking-into-internet-connected-light-bulbs. It is reproduced here for posterity.

The LIFX project started off on crowd funding website Kickstarter in September 2012 where it proved hugely popular, bringing in over 13 times its original funding target.

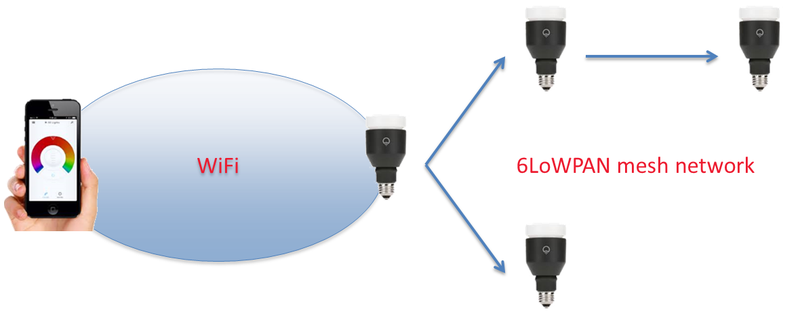

LIFX bulbs connect to a WiFi network in order to allow them to be controlled using a smart phone application. In a situation where multiple bulbs are available, only one bulb will connect to the network. This “master” bulb receives commands from the smart phone application, and broadcasts them to all other bulbs over an 802.15.4 6LoWPAN wireless mesh network.

WiFi and 802.15.4 6LoWPAN Mesh Network

In the event of the master bulb being turned off or disconnected from the network, one of the remaining bulbs elects to take its position as the master and connects to the WiFi network ready to relay commands to any further remaining bulbs. This architecture requires only one bulb to be connected to the WiFi at a time, which has numerous benefits including allowing the remaining bulbs to run on low power when not illuminated, extending the useable range of the bulb network to well past that of just the WiFi network and reducing congestion on the WiFi network.

Needless to say, the use of emerging wireless communication protocols, mesh networking and master / slave communication roles interested the hacker in us, so we picked up a few bulbs and set about our research.

The research presented in this blog was performed against version 1.1 of the LIFX firmware. Since reporting the findings to LIFX, version 1.2 has been made available for download.

Analysing the attack surface

There are three core communication components in the LIFX bulb network:

- Smart phone to bulb communication

- Bulb WiFi communication

- Bulb mesh network communication

Due to the technical challenges involved, specialist equipment required and general perception that it would be the hardest, we decided to begin our search for vulnerabilities in the intra-bulb 802.15.4 6LoWPAN wireless mesh network. Specifically, we decided to investigate how the bulbs shared the WiFi network credentials between themselves over the 6LoWPAN mesh network.

6LoWPAN is a wireless communication specification built upon IEE802.15.4, the same base standard used by Zigbee, designed to allow IPv6 packets to be forwarded over low power Personal Area Networks (PAN).

In order to monitor and inject 6LoWPAN traffic, we required a peripheral device which uses the 802.15.4 specification. The device chosen for this task was the ATMEL AVR Raven [2] installed with the Contiki 6LoWPAN firmware image [3]. This presents a standard network interface from which we could monitor and inject network traffic into the LIFX mesh network.

Protocol analysis

With the Contiki installed Raven network interface we were in a position to monitor and inject network traffic into the LIFX mesh network. The protocol observed appeared to be, in the most part, unencrypted. This allowed us to easily dissect the protocol, craft messages to control the light bulbs and replay arbitrary packet payloads.

Monitoring packets captured from the mesh network whilst adding new bulbs, we were able to identify the specific packets in which the WiFi network credentials were shared among the bulbs. The on-boarding process consists of the master bulb broadcasting for new bulbs on the network. A new bulb responds to the master and then requests the WiFi details to be transferred. The master bulb then broadcasts the WiFi details, encrypted, across the mesh network. The new bulb is then added to the list of available bulbs in the LIFX smart phone application.

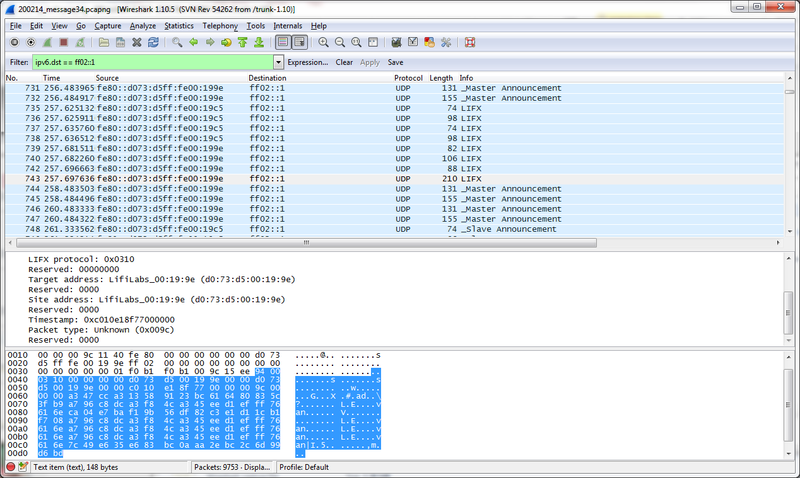

Wireshark 6LoWPAN packet capture

As can be observed in the packet capture above, the WiFi details, including credentials, were transferred as an encrypted binary blob.

Further analysis of the on-boarding process identified that we could inject packets into the mesh network to request the WiFi details without the master bulb first beaconing for new bulbs. Further to this, requesting just the WiFi details did not add any new devices or raise any alerts within the LIFX smart phone application.

At this point we could arbitrarily request the WiFi credentials from the mesh network, but did not have the necessary information to decrypt them. In order to take this attack any further we would need to identify and understand the encryption mechanism in use.

Obtaining the firmware

In the normal course of gaining an understanding of encryption implementations on new devices, we first start with analysing the firmware. In an ideal world, this is simply a case of downloading the firmware from the vendor website, unpacking, decrypting or otherwise mangling it into a format we can use and we are ready to get started. However, at the time of the research the LIFX device was relatively new to market, therefore the vendor had not released a firmware download to the public that we could analyse. In this case, we have to fall back to Plan B and go and obtain the firmware for ourselves.

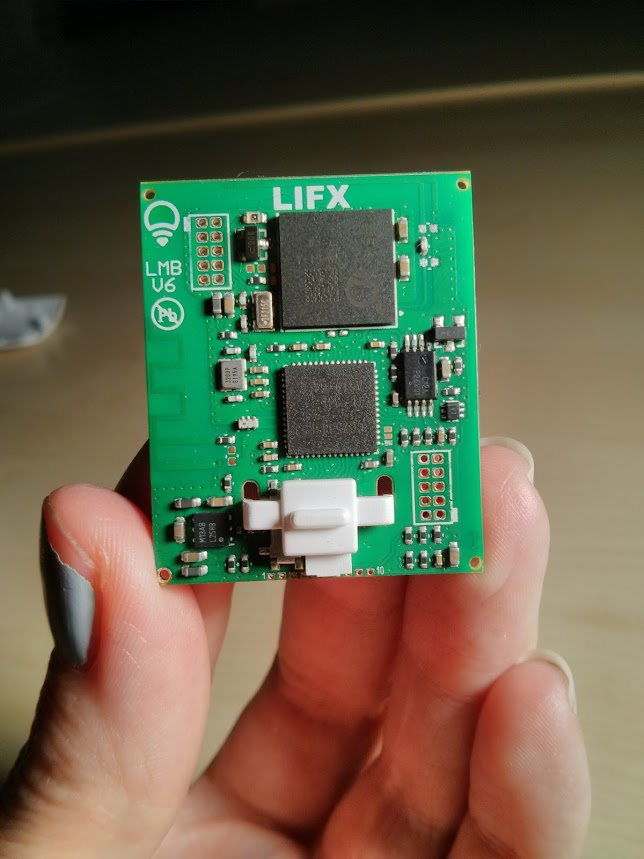

In order to extract the firmware from the device, we first need to gain physical access to the microcontrollers embedded within; an extremely technical process, which to the layman may appear to be no more than hitting it with a hammer until it spills its insides. Once removed from the casing, the Printed Circuit Board (PCB) is accessible providing us with the access we require.

Extracted LIFX PCB

It should be noted that public sources can be consulted if only visual access to the PCB is needed. The American Federal Communications Commission (FCC) often release detailed tear downs of communications equipment which can be a great place to start if the hammer technique is considered slightly over the top [4].

Analysing the PCB we were able to determine that the device is made up primarily of two System-on-Chip (SoC) Integrated Circuits (ICs): a Texas Instruments CC2538 that is responsible for the 6LoWPAN mesh network side of the device communication; and a STMicroelectronics STM32F205ZG (marked LIFX LWM-01-A), which is responsible for the WiFi side of the communication. Both of these chips are based on the ARM Cortex-M3 processor. Further analysis identified that JTAG pins for each of the chips were functional, with headers presented on the PCB.

JTAG, which stands for Joint Test Action Group, is the commonly used name for the IEEE 1149.1 standard which describes a protocol for testing microcontrollers for defects, and debugging hardware through a Test Action Port interface.

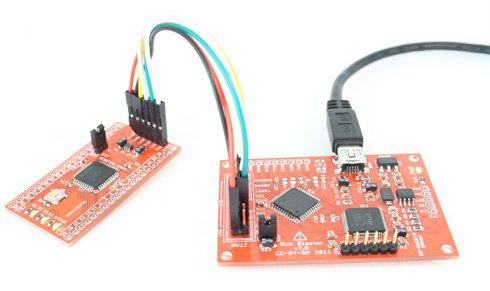

Once the correct JTAG pins for each of the chips were identified, a process which required manual pin tracing, specification analysis and automated probing, we were ready to connect to the JTAG interfaces of the chips. In order to control the JTAG commands sent to the chips, a combination of hardware and software is required. The hardware used in this case was the open hardware BusBlaster JTAG debugger [5], which was paired with the open source Open On-Chip Debugger (OpenOCD) [6]. After configuring the hardware and software pair, we were in a position where we could issue JTAG commands to the chips.

BusBlaster JTAG debugger [5]

At this point we can merrily dump the flash memory from each of the chips and start the firmware reverse engineering process.

Reversing the firmware

Now we are in possession of two binary blob firmware images we needed to identify which image is responsible for storing and encrypting the WiFi credentials. A quick “strings” on the images identified that the credentials were stored in the firmware image from the LIFX LWM-01-A chip.

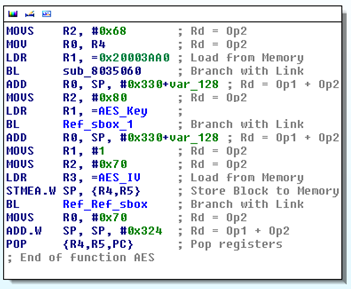

Loading the firmware image into IDA Pro, we could then identify the encryption code by looking for common cryptographic constants: S-Boxes, Forward and Reverse Tables and Initialization Constants. This analysis identified that an AES implementation was being used.

AES, being a symmetric encryption cipher, requires both the encrypting party and the decrypting party to have access to the same pre-shared key. In a design such as the one employed by LIFX, this immediately raises alarm bells, implying that each device is issued with a constant global key. If the pre-shared key can be obtained from one device, it can be used to decrypt messages sent from all other devices using the same key. In this case, the key could be used to decrypt encrypted messages sent from any LIFX bulb.

References to the cryptographic constants can also be used to identify the assembly code responsible for implementing the encryption and decryption routines. With the assistance of a free software AES implementation [7], reversing the identified encryption functions to extract the encryption key, initialization vector and block mode was relatively simple.

IDA Pro disassembly of firmware encryption code

The final step was to prove the accuracy of the extracted encryption variables by using them to decrypt WiFi credentials sniffed off the mesh network.

Putting it all together

Armed with knowledge of the encryption algorithm, key, initialization vector and an understanding of the mesh network protocol we could then inject packets into the mesh network, capture the WiFi details and decrypt the credentials, all without any prior authentication or alerting of our presence. Success!

It should be noted, since this attack works on the 802.15.4 6LoWPAN wireless mesh network, an attacker would need to be within wireless range, ~30 meters, of a vulnerable LIFX bulb to perform this attack, severely limiting the practicality for exploitation on a large scale.

Vendor fix

Context informed LIFX of our research findings, who were proactive in their response. Context have since worked with LIFX to help them provide a fix this specific issue, along with other further security improvements. The fix, which is included in the new firmware available at http://updates.lifx.co/, now encrypts all 6LoWPAN traffic, using an encryption key derived from the WiFi credentials, and includes functionality for secure on-boarding of new bulbs on to the network. Of course, as with any internet connecting device, whether phone, laptop, light bulb or rabbit, there is always a chance of someone being able to hack it. Look forward to our upcoming blogs for more details.

References

[1] http://lifx.co

[2] http://www.atmel.com/tools/avrraven.aspx

[3] http://www.contiki-os.org/

[5] http://dangerousprototypes.com/docs/Bus_Blaster

[6] http://openocd.sourceforge.net/

[7] http://svn.ghostscript.com/ghostscript/tags/ghostscript-9.01/base/aes.c